On March 16-18 the Swedish Dialogue Institute for the Middle East and North Africa, together with Sida Partnership Forum, UN Women, UNEP, and Stockholm Environment Institute, co-hosted the 2021 SIDA Global Learning Experience. With over 150 participants from approximately 100 different organizations, the event focused on gender, environment, and climate. The Dialogue Institute hosted the MENA hub, which addressed these challenges in the context of the Middle East and North Africa, where they are particularly severe. The discussions in the MENA hub focused on the nexus of gender, climate and security, with special attention given to gender and water security.

People and Planet: Gender, Environment and Climate in the

2030 Agenda – report from the MENA Hub

16-18 March 2021

Executive Summary

On March 16-18 the Swedish Dialogue Institute for the Middle East and North Africa , together with Sida Partnership Forum, UN Women, UNEP, and Stockholm Environment Institute, co-hosted the 2021 SIDA Global Learning Experience. With over 150 participants from approximately 100 different organizations, the event focused on gender, environment, and climate. The Dialogue Institute hosted the MENA hub, which addressed these challenges in the context of the Middle East and North Africa, where they are particularly severe. The discussions in the MENA hub focused on the nexus of gender, climate and security, with special attention given to gender and water security.

Participants identifed a number of obstacles to gender equality and female empowerment in addressing water and climate issues, including a lack of meritocracy, the absence of good data, ineffective policy interventions, inappropriate working environments, and conservative social attitudes/lack of political will. But they also presented solutions to these challenges, including improving governance, using gender-based household data, utilizing gender budgeting techniques, modernizing working hours, and overcoming resistance to change in various ways. To advance a progressive agenda on these issues and support female efforts, participants suggested regular meetings and exchanges amongst Sida partners working in this field. The Dialogue Institute would be interested in engaging with such initiative and playing a coordinating role.

Introduction/Context

Climate change is impacting every corner of the globe, and severe droughts and rising temperatures are leading to food insecurity and loss of livelihood in many regions. Yet though climate change affects us all, people experience its impact differently based on, for instance, gender, socio-political and economic factors. Gender equality as a lens for climate and environmental work ensures women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life. Women carry significant knowledge about preserving biodiversity and natural resource management and are as such important agents of change

Given the importance of the nexus of gender, climate, and environment, the 2021 SIDA Global Learning Experience addressed the intersection of these three topics through a variety of global, thematic and regional ‘hub’ sessions over the course of a three-day digital conference on March 16-18. The aim was to strengthen organizational capacity to integrate gender-based approaches within climate and environmental programmes, projects and processes of relevance to development cooperation.

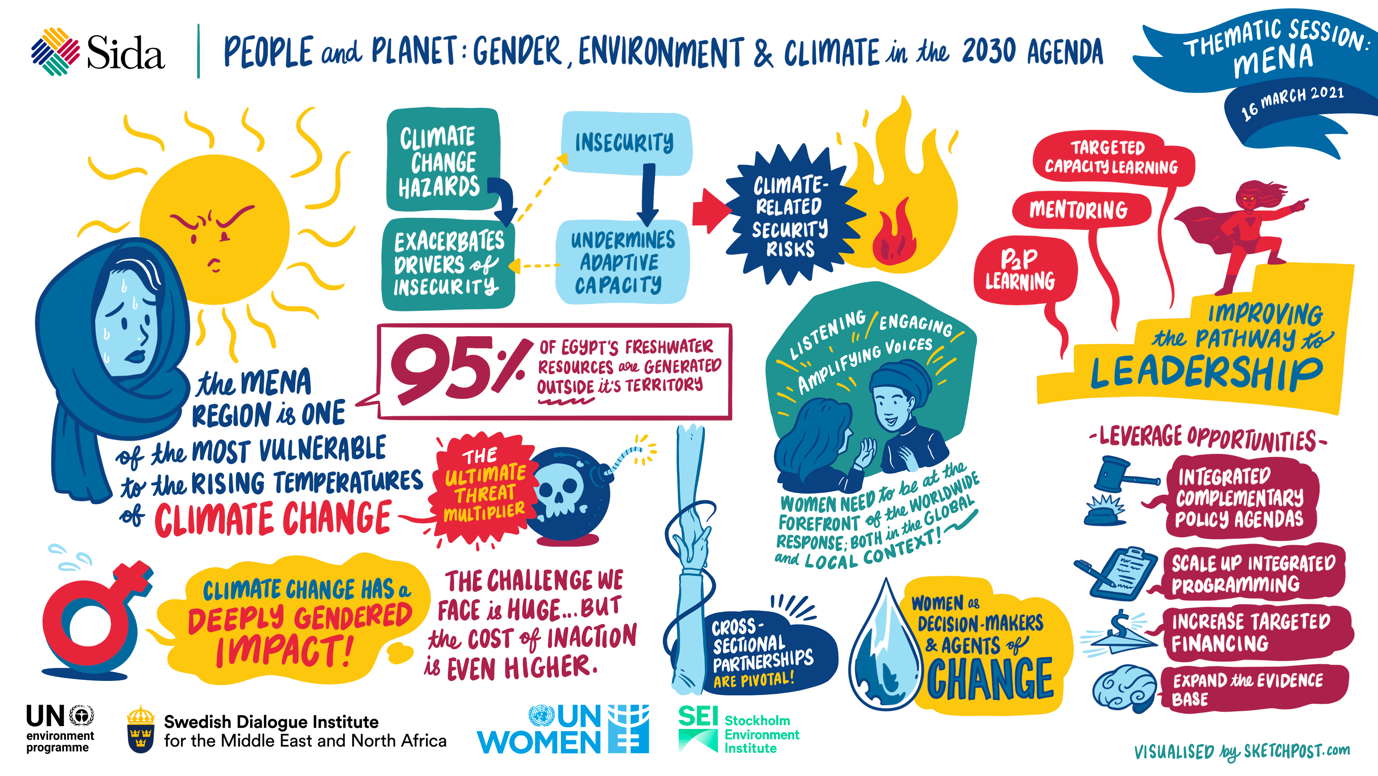

The MENA hub, hosted by the Swedish Dialogue Institute for the Middle East and North Africa, focused on the challenges of gender, climate, and environment in the context of the Middle East and North Africa, where they are particularly severe. Over 60 per cent of the region’s population lives in areas where access to water is limited, and the UN forecasts suggest that the Middle East will be hit hard by climate change in coming decades.

Given that the MENA region has endured several intractable armed conflicts, severe water stress and significant economic losses related to environmental degradation in recent decades, the discussions in the MENA hub were focused on the nexus of gender, climate and security, with special attention given to gender and water security.

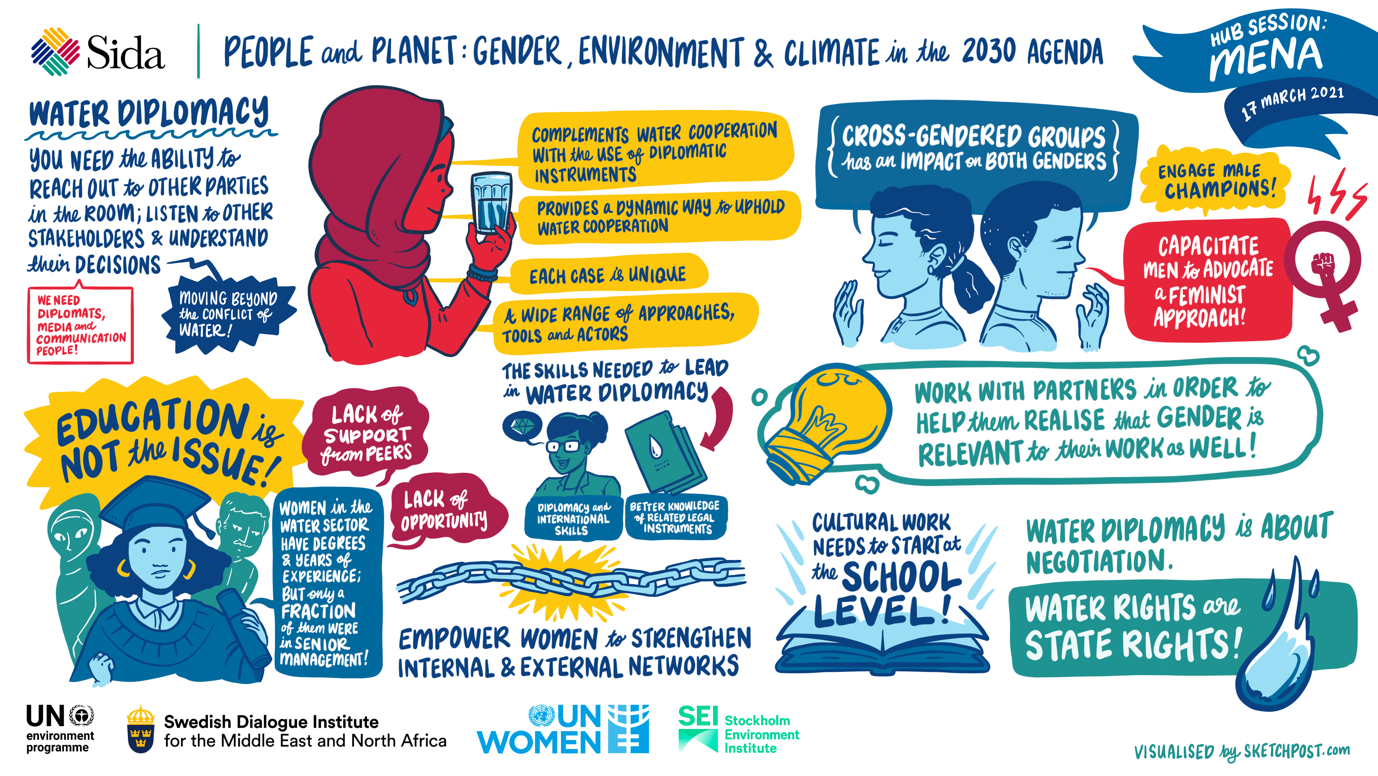

The programme in the MENA hub started with a thematic session, where the UN study "Gender, climate and security - sustaining inclusive peace on the frontlines" (see report here) was presented by Molly Kellogg (UNEP) and Dr. Marisa Ensor (Georgetown University). This was followed by a panel discussion featuring Elizabeth Yaari (Stockholm International Water Institute/Siwi) and Kirsten Winterman (Middle East Desalination Research Center/MEDRC) as well as Kellogg and Ensor. During the second day the MENA hub had a presentation of a recently launched study on Empowering Women in Water Diplomacy in the MENA region produced by Global Water Partnership-Mediterranean and the Geneva Water hub. Most of the programme was otherwise devoted to networking amongst partners, and the exchange of knowledge and experiences in peer-to-peer learning.

Below are some of the main findings and recommendations.

Obstacles to gender equality and women’s empowerment

A general lack of meritocracy limits the opportunities for women to advance into positions of leadership and responsibility. The absence of meritocracy reflects a number of well-documented phenomena, including autocratic structures, weak institutions, nepotism, corruption, and political patronage. While these factors also prevent the advancement youth, minorities, and other under-represented groups , women are particularly hard hit, given existing social norms (see below), which was attested to by participants.

A lack of accurate, high-quality and relevant statistical data complicates effective analysis and policy formulation. Many participants highlighted, in particular, the scarcity of gender-disaggregated data (data collected and tabulated separately by gender), which allows for the measurement of male-female differences on a variety of social and economic dimensions. Gender-differentiated information is a pre-requisite for effective, appropriate, and evidence-based analysis and policy proposals, and thus its absence is a real obstacle.

A history of ineffective and insufficient policy interventions to address challenges for women in the region have contributed to slow progress. There has been a relative lack of policies contributing to gender-balanced economic and social progress in the region. Fiscal and social policies have not sufficiently targeted women’s needs, in terms of, for example, labour market participation and health care, and hence the role of women in the MENA region continues to lag behind.

Old-fashioned and inappropriate working environments hinder women’s participation in the labour force. When key discussions take place in spaces that women do not have access to, they are prevented from participating effectively in the labour market. One female negotiator spoke of “work and decisions often happening after hours, for instance at the pool”. So despite being technical experts, female negotiators are sometimes excluded.

Conservative social attitudes and lack of political will combine to make progress for women in the region slow and uneven. Several participants mentioned remaining prejudices that women cannot have senior or decision-making positions, either due to a percevied lack of competence or a questioning of their ability to take care of domestic responsibilities while also fulfilling their work obligations (the implicit assumption being that men cannot or will not do their part in the home). One woman said, “Women are often talked about, but not spoken to.” Others mentioned challenges for some women to take certain jobs, which require travel or where they would be the only woman in the room, for cultural reasons: “As competent and as ambitious as I am, I don't want to bring shame on my husband,” said one woman. Finally, given the slow rate of change, some participants pointed insufficient political will amongst the establishment to push for greater gender equality, even if change is happening.

Improving the prospects for gender equality

Strengthening governance and meritocratic processes. By addressing the issues outlined above – nepotism, corruption etc – through objective recruitment processes, greater transparency, and a host of other good-governance reforms, the prospects for gender equality would be greatly enhanced. Women are well-educated, competent, and have sufficient experience, but need institutions that allow them to develop and thrive.

Addressing statisticial shortcomings. Ideally, gender-disaggregated data will become more readily available in the future, though that will probably require greater investment in data collection. Another option mentioned in the seminars is to rely on gender-based household surveys, which ask women and men how much time they spend on different activities, so as to quantify their time distribution. This, too, will necessitate more resources.

Designing appropriate policy proposals. Several participants argued that reforms can be facilitated through the process known as gender-budgeting, which is the application of gender mainstreaming in the budgetary process. More specifically, it refers to “a gender-based assessment of budgets, incorporating a gender perspective at all levels of the budgetary process and restructuring revenues and expenditures in order to promote gender equality”. The output would, for instance, include intiatives that help women enter and establish themselves in the labour market, through education, vocational training, pro-work tax policies, and targeted benefits. More ambitiously, various participants emphasized the need to move from gender mainstreaming to gender transformation.

Modernizing working conditions. The practice of conducting key work processes or decision-making in the evenings or in places where women cannot participate is clearly suboptimal. Instead, work should be concentrated to normal working hours, where all staff can participate equally. Pushing for these changes requires strong will and courage, and can be difficult, as one participant explained. To bring about more effective working practices, staff need support from female and male champions, existing leaders, and donors.

Overcoming resistance to change. A number of suggestions to drive change emerged in the discussions. Supporting emerging leaders is crucial, for instance through professional networks that create safe spaces for women to exchange experiences and learn from each other. Peer-to-peer activities, capacity building, and mentorship can also be very useful. Campaigns and efforts to raise awareness of gender-related issues remain essential, but need to be complemented by other change agents, such as male champions and donors. Men should model expected behaviour, push for gender equality, and support promotions of women. Some women flagged the risk of “false champions”, men who professed to support efforts to improve the position of women, but then failed to act when opportunities arose: “Some male leaders will welcome women into junior and advisory positions, but not as real decision-makers.” Ultimately, it is about building coalitions for change, which bring together relevant actors and interest groups, including men, women, youth, and figures from the establishment. Donors can emphasize the importance of including women and giving them real responsibility, but genuine change comes from within institutions, particularly from men in leadership positions.

Advancing the agenda: proposed next steps

As this summary has indicated, a plethora of constructive and useful ideas was put forward during the discussions, and participants in the MENA hub showed an interest for further collaboration on both an individual and institutional level. Many participants expressed a desire to maintain, develop, and expand this emerging network of professionals active on gender, climate change, environment, security, and water diplomacy, in the MENA region. After the conference, Dr. Ensor expanded on these themes, while referencing the Global Learning Event, in a post for the Wilson Center for Scholars’ New Security Beat blog, No Peace Without Water, No Water Without Peace, and Neither Without Women’s Empowerment (see post here).

A sustainable, effective network typically requires a host or convenor – an organization that can co-ordinate the network’s participants, propose future meetings, and organize gatherings. It was suggested that the Dialogue Institute could play this role. The Institute could potentially be willing to take on a coordinating role, ideally in close cooperation with Sida’s regional MENA team in Amman and in dialogue with other organizations involved.